Are extended sales events boosting profits or inflating numbers? Discover why data and tech investments are key to decoding retail sales success.

Many retailers’ dominant mode of thought has been to run sales when they want, but keep special events special. Big holidays, Black Friday, and Friends and Family events were separated from the broader pool of general sales. Then came Cyber Monday, extending the usual Black Friday one-day shopping extravaganza through the entire weekend, and the floodgates opened.

Retailers are increasingly asking whether these longer sales actually result in a more profitable event. Amazon just asked this question when it extended Prime Day 2025 to four days. But the answer is surprisingly complicated.

Is longer really better?

Retail price calculations are challenging enough, and the difficulty only increases as discounting comes into play. A common way of simplifying things is asking: “Well, did we get more sales this year than last?” That flattening is tempting, since topline growth has become the headline metric for much of the general conversation around retail and business.

The formula is simple: You generated revenues of $X last year and $Y this year. If $Y > $X, extending the sale was a good idea. By that logic, most sales extensions are a resounding success.

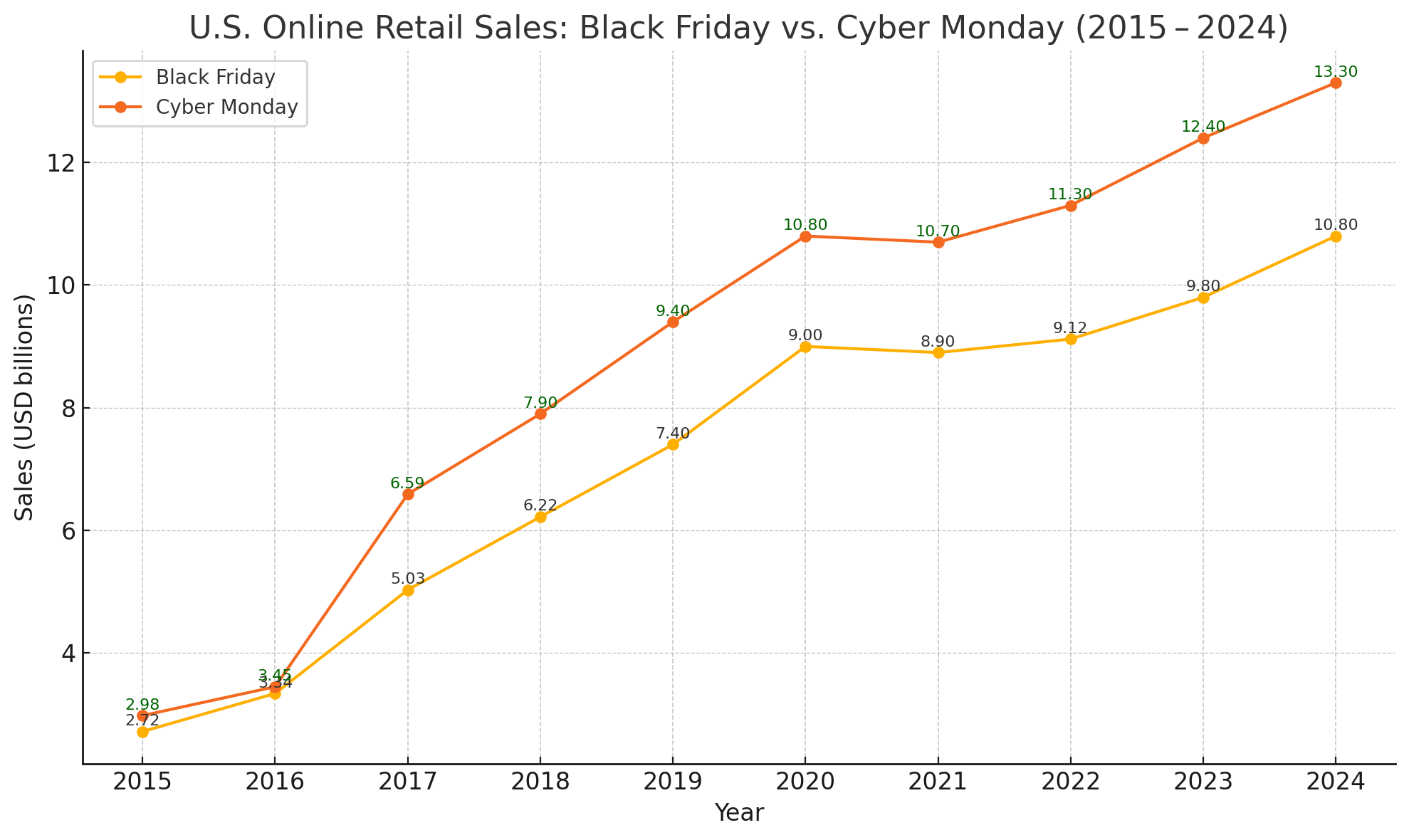

The chart below plots estimated U.S. sales across Black Friday and Cyber Monday using nominal dollars, with sources used as consistently as possible. This post-Thanksgiving event is a good proxy, thanks to abundant available data, its iconic status, and its role as the poster child for extending once-limited sales to almost hilarious proportions.

The chart shows why the simplified view holds so much power. At first glance, the longer the post-Thanksgiving sale season lasts, the more money it brings in (assuming the pace of extension has stayed steady). But that conclusion, while tempting, is entirely incorrect.

The chart shows why the simplified view holds so much power. At first glance, the longer the post-Thanksgiving sale season lasts, the more money it brings in (assuming the pace of extension has stayed steady). But that conclusion, while tempting, is entirely incorrect.

The Calculus of Retail Pricing

Top-line numbers may look impressive, but they’re far from the best measure of a sale’s success. Large, data-driven retailers like Amazon employ entire departments of retail analysts and economists to try to pull apart the complex layers that go into evaluating sales extension periods. These layers include:

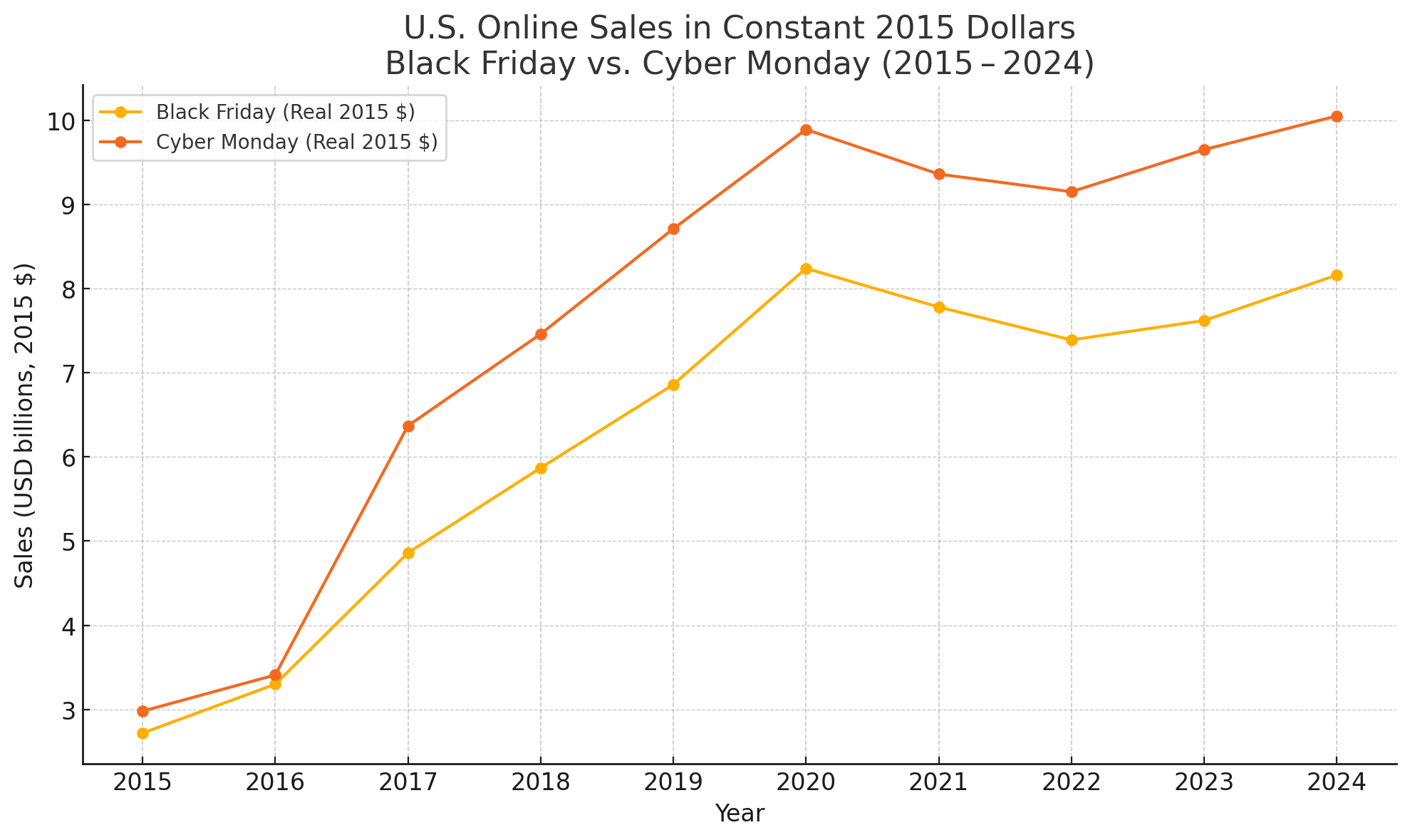

Inflation: Look at the graph below. It’s the same data set as before, but it’s adjusted for inflation this time, using 2015 dollars as a constant. The numbers still go up, but not nearly as much, and barely hold even in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Costs: Inflation does not accurately reflect the reality of increased costs of goods sold (COGS), as most retailers are rarely in a position to pass 100% of cost increases on to consumers. In the age of trade wars, this matters even more for import-heavy sectors like electronics or apparel, where duties cut into margins above and beyond what CPI inflation numbers reflect.

Costs: Inflation does not accurately reflect the reality of increased costs of goods sold (COGS), as most retailers are rarely in a position to pass 100% of cost increases on to consumers. In the age of trade wars, this matters even more for import-heavy sectors like electronics or apparel, where duties cut into margins above and beyond what CPI inflation numbers reflect.

Marginality: This is where the economists get really excited. Benefits don’t scale linearly. Sometimes, each additional sale is worth more — for example, if you’re trying to hit a fixed-cost threshold and you haven’t yet reached the breakeven line. Or, each sale is worth less — say, when low-margin items siphon production capacity away from high-margin ones, eating away at profitability per item sold.

This gets especially complex when evaluating sale extensions because, as the sale runs longer, your chances of selling an item at a discount to a customer who would have bought it at full price dramatically increase.

Think about going to the grocery store to pick up something for dinner and only realizing at checkout that the ground beef you were prepared to pay full price for was actually 25% off that week. That discount becomes a loss to the retailer. When Amazon extended its Prime Day sale from one day to four, it attracted new buyers. However, it also saw a surge in buyers who signed in during day three, simply because they were already planning to buy an item and received a discount.

Time-shifted sales: Imagine planning to purchase a new flash drive. You’ve needed one for a while and are finally ready to order it, but then you hear that Prime Day will be bigger, longer, and more intense this year than ever. You’ll wait until the sale to check out and see what kind of deal you can get. You may even put off the purchase until the last day of the sale, just in case the discounts get steeper.

This timeshifting of consumer behavior results in lower profits per customer and can artificially inflate topline sales while hurting quarterly growth. If everyone holds off on making big purchases in June to make them during Prime Day, Q2 sales will be lower, and Q3 sales may be lower overall.

Pulling Signal From Noise

Amazon believes its plan is paying off. After a trial run with extended Big Savings Days, the platform pressed on ahead with a longer Prime Day(s) event and seemed optimistic about the results in a post-event press release. However, the language in this release emphasizes savings for customers and topline numbers. Despite being a company that generates substantial revenue from data processing, even Amazon may not be sure of the value of the extended event.

The bottom line for retailers: It’s no longer enough to play fast and loose with evaluating the success of discounting strategies and sale events. Investing in data — from architecture and storage to processing and analysis — is critical to making these decisions, especially going forward.

This will become more critical as AI matures and integrates into dynamic pricing models, helping retailers squeeze the most profitability out of every transaction. Sales events are no longer the domain of chief marketing officers; they belong to the CIO now.

So is longer better? Maybe. Amazon seems committed to the approach, and if anyone has the processing power to calculate value, it’s the team behind AWS. But still, the answer isn’t a simple “yes” or “no.”

Pricing is complicated. Different retailers may find other strategies, depending on the outcomes they’re optimizing for. But the only constant is that success requires investment in technology, processes, and expertise to go deep into the data and extract real insight.